The Fourth Trimester: The Months We Forget Mothers

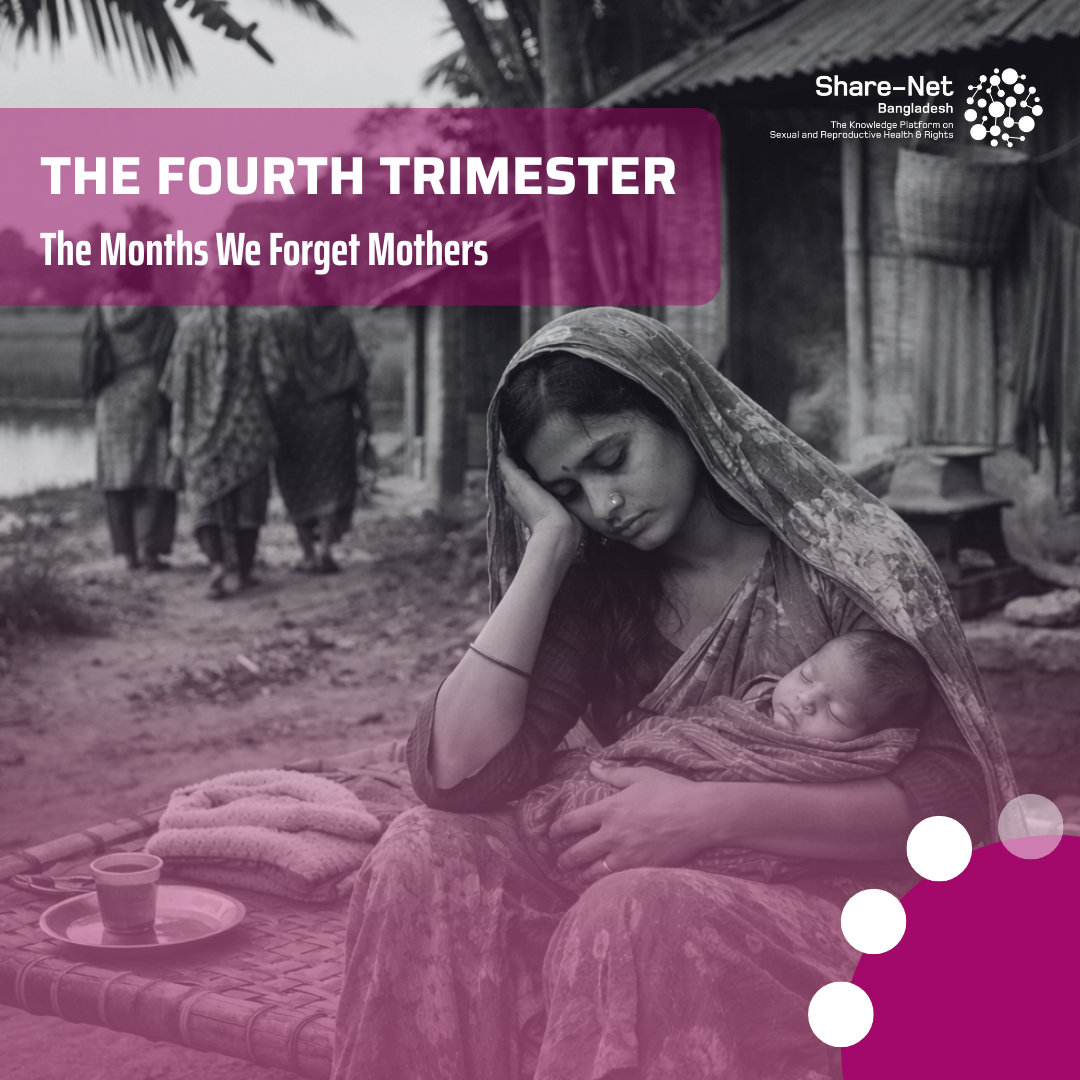

Childbirth is often treated as the finish line. The baby is born, the danger has passed, congratulations are offered, and life is expected to return to normal. However, the most fragile period begins only after delivery for millions of women. This overlooked phase is known as the “fourth trimester”, the first twelve weeks after childbirth, when a woman’s body, hormones, identity and mental health are all in transition.

Scholars and Doctors describe the fourth trimester as a time of intense physical recovery, emotional adjustment and psychological vulnerability. Sleep deprivation, hormonal shifts and the sudden responsibility of caring for a newborn collide, often without adequate support. Unlike pregnancy, which is closely monitored, the postpartum period remains largely invisible.

Globally, the consequences are clearly visible. WHO estimates that around one in five women in low and middle-income countries experience postpartum depression or anxiety. A landmark Lancet Psychiatry series has shown that untreated maternal mental health conditions affect not only mothers but also infant development, bonding and long-term child wellbeing. In high-income countries, studies from Harvard Medical School and the UK’s National Health Service have linked postpartum mental illness to increased maternal mortality through suicide, now recognised as a leading cause of death in the year after birth.

In Bangladesh, the picture is even more concerning. Research published in the Journal of Affective Disorders suggests that between 18 and 35 per cent of Bangladeshi mothers experience depressive symptoms after childbirth. Yet mental health screening during postnatal care remains rare. Most postnatal visits focus on the baby’s weight, vaccines and feeding, while the mother’s emotional state is barely addressed.

When the visitors leave, and the celebrations fade, many women find themselves alone with fear, guilt and exhaustion. Postpartum mental health challenges go far beyond depression. Anxiety, panic attacks, post-traumatic stress following complicated births and, in rare cases, postpartum psychosis are all part of this hidden landscape. These experiences are rarely spoken about, often dismissed as weakness or hormonal mood swings.

The care gap is structural. Health systems are designed to prioritise delivery, not recovery. Globally, policies such as the WHO’s recommendations on postnatal care call for mental health screening and counselling, but implementation remains uneven. Bangladesh’s National Maternal Health Strategy acknowledges postpartum care, yet mental health services are still limited, especially outside urban centres.

Cultural expectations deepen the problem. New mothers are expected to “bounce back”, manage household duties and express gratitude rather than distress. Emotional pain is often silenced in the name of resilience. For women facing poverty, domestic violence or limited family support, the risks multiply. Inequality shapes who gets help and who is left behind.

Listening to mothers reveals the human cost. Many describe feeling invisible once the baby arrives. They speak of crying in silence, fearing judgment and believing their suffering is a personal failure rather than a systemic one.

Real support must move from policy to practice. This means routine mental health screening during postnatal visits, community-based counselling, trained midwives who ask how the mother is coping, and longer paid maternity leave. It means recognising that caring for the mother is essential to caring for the child.

Reframing recovery requires a simple shift in perspective. Birth is not the end of care; it is the beginning of a new, vulnerable chapter. Until the fourth trimester is taken seriously, mothers will continue to suffer in silence, long after the delivery room lights are turned off.

Sources:

- WHO

- Lancet Psychiatry Series