Bangladesh’s Next Frontier: From Medium Development to Meaningful Progress

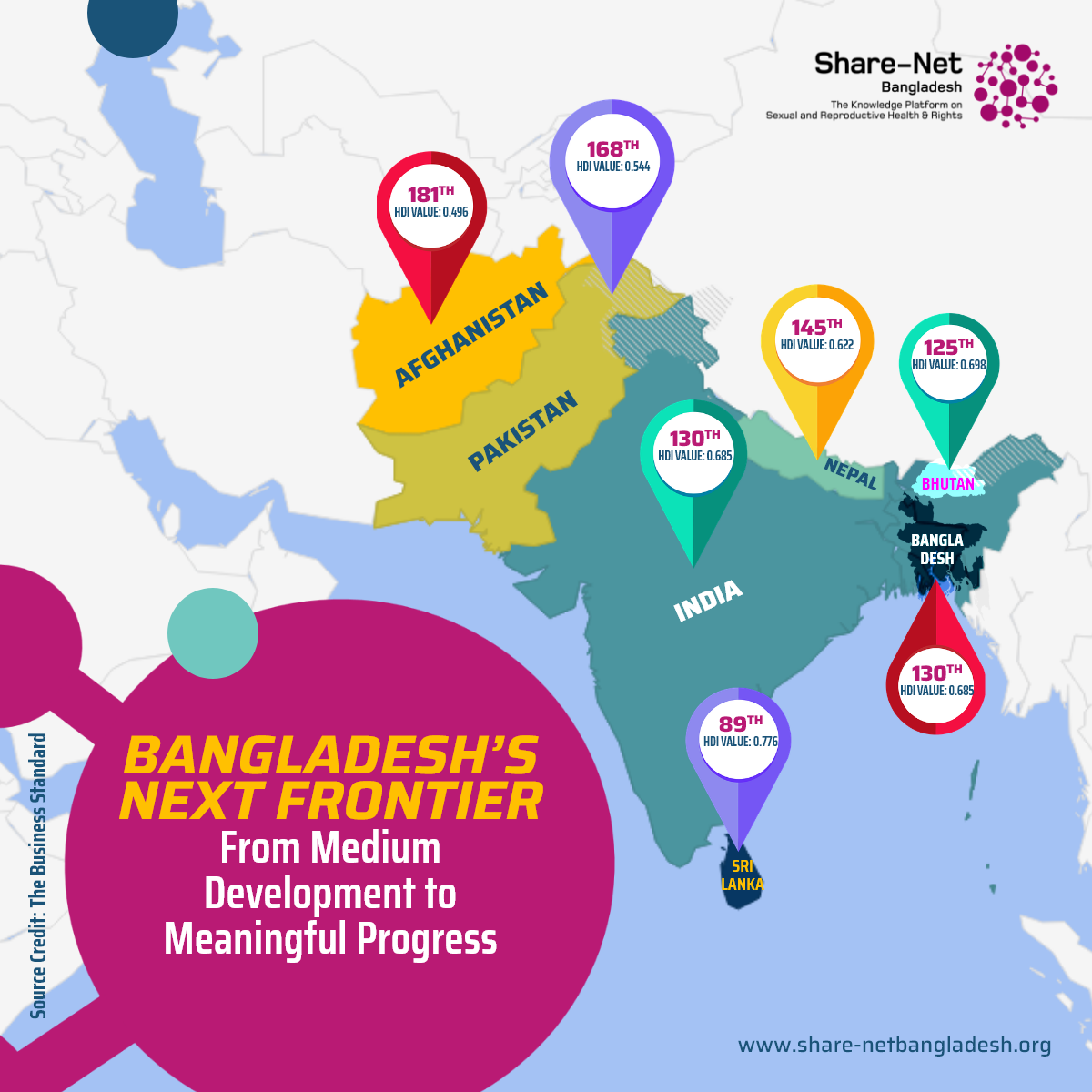

Bangladesh has inched forward in the 2023 Human Development Index (HDI), now ranked 130th among 193 countries. Yet, beneath this statistical pat on the back lies a persistent reality: the country remains stuck in the “Medium Human Development” category, a label it has carried since 2009. For a nation often touted as a development miracle in South Asia, this stagnation raises critical questions — especially when viewed through the lens of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).

The latest UNDP Human Development Report, titled “A Matter of Choice: People and Possibilities in the Age of AI,” gives credit where it’s due. Bangladesh’s HDI improved from 0.680 to 0.685, thanks to gains in health and income. Life expectancy has ticked up to 74.67 years, and Gross National Income (GNI) per capita climbed from $8,114 to $8,498. But scratch the surface, and the gloss fades. The education indicators — a fundamental pillar of human development — have flatlined. Mean years of schooling remain at 6.79, and expected years of schooling for children stands at 12.31. No change from last year.

What’s more concerning is the gap between these gains and the lived realities of millions — particularly women, adolescents, and marginalised communities. When HDI is adjusted for inequality, Bangladesh’s score drops sharply to 0.482, a staggering 29.64% loss. This is more than just a number — it reflects systemic barriers that continue to hold back those furthest behind.

SRHR: The Unspoken Factor in Human Development

One of the most overlooked drivers of stalled human development is the state of SRHR in the country. Without significant improvements in this area, any progress on HDI will remain cosmetic at best.

Start with child marriage — still one of the highest rates in the world. According to UNICEF, 51% of Bangladeshi girls are married before the age of 18. Early marriage truncates education, increases maternal mortality risks, and perpetuates poverty. These girls are often denied access to menstrual hygiene management (MHM), comprehensive sexuality education, and modern contraception — basic tools for autonomy and health.

Gender-based violence (GBV) continues to shadow the lives of many women. UNFPA reports that 72.6% of ever-married women have faced some form of intimate partner violence. The emotional, physical, and psychological toll of GBV doesn’t just diminish individual potential — it drags down the nation’s collective human development.

The country’s Gender Inequality Index (GII) remains stuck at 0.487, ranking Bangladesh 125th out of 172. There has been no progress since 2022. This stagnation is both a symptom and a cause of the broader development slowdown.

Access to menstrual regulation (MR) and safe abortion services also remains restricted, particularly for rural, poor, and unmarried women. Lack of awareness, stigma, and inadequate services prevent many from exercising their reproductive rights. The implications go beyond health — they touch dignity, choice, and equity.

A Shift in Priorities, Not Just Numbers

For Bangladesh to rise above the “medium” ceiling, it needs more than incremental gains in income or life expectancy. It requires a transformative shift in how the state invests in people — particularly in SRHR.

That means integrating comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) into the national curriculum, not as an afterthought but as a core subject. This means improving access to youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in every district — not just in urban centres. This means ending legal and social barriers that criminalise choice, silence survivors, and stigmatise reproductive decisions.

Moreover, data must be disaggregated by gender, age, geography, and socio-economic status. Development can’t be inclusive if it doesn’t count — or account for — those most marginalised.

Beyond the Numbers

The report warns that if the world’s current sluggish pace continues, the 2030 goals of “very high” human development may be delayed by decades. For Bangladesh, the warning is especially urgent. The country can no longer afford to celebrate progress in isolation while inequality festers underneath.

Bangladesh’s demographic dividend — its vast youth population — offers hope. But hope alone won’t move the needle. The country must put rights, equity, and access at the centre of its development strategy. SRHR isn’t a side issue. It’s central to human development. And until that’s recognised at the highest levels of policy and investment, Bangladesh will remain a country of potential — not promise.

Source: The Business Standard