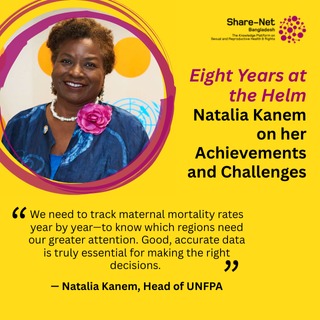

Eight Years at the Helm: Natalia Kanem on her Achievements and Challenges

Interview with Natalia Kanem, the Head of UNFPA

Natalia Kanem, head of the United Nations sexual and reproductive rights agency UNFPA, is retiring from her long-standing position. After eight consecutive years in this key leadership role, she is stepping down. During her tenure, she defended the rights of women and adolescent girls amid a global pandemic, ideological opposition, and political instability. Before her departure, she gave an interview to UN News’ Mita Hosali, where she highlighted UNFPA’s main achievements under her leadership and what kind of support adolescent girls will need in the future.

Natalia Kanem: In short, UNFPA has upheld the rights and choices of women—especially adolescent girls—in the field of sexual and reproductive health and rights. We have trained millions of midwives. During this period, we have supplied hundreds of millions of contraceptive units. We have modernised our service delivery capacity to the highest level—meaning shorter queues and women receiving care close to home. UNFPA has also achieved remarkable success in expanding humanitarian assistance, which was crucial given the high demand.

We have also established a perspective: while it’s important to discuss global population issues, those discussions should be seen through the eyes of a 10-year-old girl entering adolescence. Will she be able to stay in school, graduate, and build a life? Or will her rights and choices be curtailed by child marriage, female genital mutilation, or extreme poverty?

So, I would say this journey has been very exciting for me. Though there were some frightening moments, I’m always impressed by how my UNFPA colleagues have completed their work with sharp foresight and big hearts.

Mita Hosali: You are leaving at a time of crisis and uncertainty—when major donors, including the United States, have stopped contributing large sums, and reforms are leading to staff cuts. What would be your message to staff who work in the field every day, month, and year—and also to the outside world?

Natalia Kanem: UNFPA staff are extraordinary. We operate in 151 locations with over 5,000 people. Our staff have weathered many storms. But things are more complex now, because multilateralism is being questioned at a time when it’s needed more than ever.

Our Secretary-General has played an excellent role in this regard. I remind staff: every morning, we get up to push forward an agenda that accelerates human development, makes families closer and more compassionate, and always remembers—what will that 10-year-old girl do? What will she achieve as she grows up?

Our funding—especially from the United States—has never been entirely stable. When they give, they’re a major donor; when they don’t, we feel it. But we have prepared to diversify budgets and funding sources. In my tenure, last year our budget was USD 1.7 billion—the highest in our history. But we never take this for granted.

I tell my team we must prove ourselves every single day. If we make mistakes, we must correct them and find new friends. For example, I just came from Seville, where a development financing proposal achieved great success. Despite concerns about debt, economic instability, and global unrest, UNFPA has worked very well there with our banking and innovation partners. In Kenya, they launched a new development fund that provides sexual and reproductive health and rights information to help keep adolescent girls in school. In a two-year pilot, they achieved double their target and generated huge interest.

I think when our programmes face obstacles, the wise thing is to remind people that every life matters—and that funding cuts have devastating effects on women and adolescent girls. Because in crises like climate change, conflict, or migration, women suffer most. They lose access to healthcare; they can’t safely attend school. We must speak the truth—and speak it in ways that gain everyone’s support.

Mita Hosali: You mentioned conflict. I recall at the start of your tenure, you, the Secretary-General, and other officials visited Cox’s Bazar and spoke about life-saving services for Rohingya women and children. Now, years later, there are more conflicts—Ukraine, Sudan, Gaza—and older conflicts continue. In such situations, when funding stops, what is the real-life impact?

Natalia Kanem: I think the need for humanitarian assistance has risen dramatically over the past decade. Women and adolescent girls are always among the hungriest. In terms of healthcare, they’re overlooked—often prioritising other family members first. And in crises, sexual and gender-based violence increases alarmingly.

It’s vital for the UN to stand by UNFPA and all our partners—defending people’s dignity wherever they are. In places like Cox’s Bazar or Haiti, the safe spaces UNFPA can provide—maybe just a tent decorated with crayons—become symbols of comfort for women in crisis.

In Ukraine, I think the mental health counselling services we can provide make a huge difference. When everything around you is gone, your biological needs—things that can be embarrassing for an adolescent girl, like menstruating in a refugee camp—must be met in ways that preserve dignity. That’s why we call them “dignity kits.” The contents—whether toothbrushes, sanitary pads, blankets, or shawls—are decided by the community. They give temporary relief from desperate situations and remind you that you will fight to survive another day. That’s the UN’s job—to help ensure that brighter day eventually arrives.

Mita Hosali: Of course, UNFPA, like other development agencies, mainly achieves progress step-by-step. One such area is female genital mutilation (FGM), which has been addressed for many years. I know UNFPA has worked strongly on this issue in recent years. We’ve covered it at UN News. This is a topic I personally care about. Have you seen real-life examples where lawmakers, working with civil society, have managed to stop this practice or make it completely unacceptable?

Natalia Kanem: That’s the reality—changing mindsets is what truly changes a girl’s life, even within her own family. Her community, religious and other leaders, her teachers—everyone at all levels of society—must move toward changing that mindset.

I believe UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women, and many others are working strongly against child marriage, FGM, and gender-based violence, and it’s making a huge impact. Many adolescent pregnancies are not voluntary but forced—and these efforts are making a big difference.

We see it in statistics: for example, maternal mortality has dropped by 40% in the past two decades. That’s a huge achievement—showing a health system that prioritises women. We’ve also successfully raised awareness that young, malnourished women face greater risks during pregnancy.

In FGM, we’ve made significant progress. But COVID slowed it down—girls out of school were in communities where FGM was carried out hastily.

We’ve seen many young people speak out against FGM. And when someone from the same cultural background stands beside their own community’s youth, it’s always more effective.

Even in Indonesia—where high population means high numbers of FGM—we’ve seen declines. But it’s not something that ends overnight; patience and persistence are needed. If we succeed, the whole community benefits.

That’s why it’s so important for religious and traditional leaders to oppose harmful practices—and to work with school systems so girls understand the risks and can make better choices for themselves.

Mita Hosali: You mentioned the drop in maternal mortality. I know UNFPA is now more engaged in data-driven work—like using data dashboards. We know, for example, that there are now over 8 billion people globally, India has overtaken China in population, and life expectancy has risen significantly to about 73 years.

But I imagine concerns remain. Have we made similar progress in meeting women’s and girls’ sexual health and basic needs? How do we protect these gains while also prioritising women and girls still left behind?

Natalia Kanem: For me, data tells the story—and it’s a story worth shouting from the rooftops. My predecessor, the late Dr Nafis Sadik, used to say, ‘If you want development, put women and girls at the centre.’ And every data point shows they’re the most at risk of being left behind.

This isn’t about one continent—it’s the same within and between countries. That’s why we’ve tried to use data as a tool to help lawmakers create better laws and families make better decisions.

This year, our State of World Population report highlighted something the UN hasn’t often emphasised: comprehensive reproductive questions. We asked women if they wanted one, two, or three children. We asked men why they couldn’t achieve their desired family size. Most cited economic reasons, housing issues, and doubts about being good parents amid uncertainty.

Previously, we also noted that only half of all pregnancies globally are planned. Almost half are so-called “unintended”. Sometimes that’s joyful, but often it disrupts a young woman’s life plans.

We must make this data more accessible. Our Population and Data division has spent much time helping countries prepare for censuses—country by country.

When something matters, counting it and monitoring its progress can change everything.

I’m also concerned that funding cuts may cause the loss of key databases. We need to track maternal mortality rates year by year—to know which regions need our greater attention. Good, accurate data is truly essential for making the right decisions.

Source: UN News Interview, July 2025